FR I EN

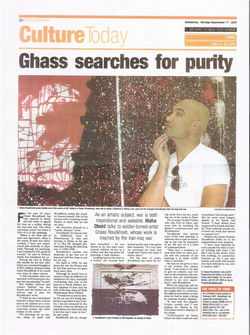

The international artist, praised both for his artistic work and his humanitarian commitment, stands out for his ability to challenge the conventions of the art market with profound creativity and remarkable sensitivity. His versatile artistic approach, blending painting, drawing, and sculpture, takes the audience on a true emotional journey.

For Ghass, art is not just a form of personal expression but becomes an intimate and intergenerational bond. It is a universal language, connecting people across time, conveying a poignant message that embraces the past, the present, and the future.

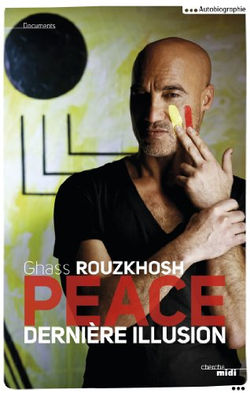

Ghass' creations emerge from a deep and compelling source, revealing a palpable urgency: the need to bring his vision of the world to life. His painful journey, marked by war and violence, is reflected in his work, but rather than being entirely defined by these dark experiences, his art transcends them.

Each piece tells a story, capturing the complexity of human emotions with a depth that goes beyond words. Ghass’ aesthetic, sometimes profoundly shaped by tragedy, reflects an exceptional sensitivity.

His different artistic periods embody deep meanings, ranging from passionate red to blue, symbolizing the recently incorporated energy, evoking the evolution of his emotions and message over time. Despite his painful past, Ghass continues to eloquently convey a message of peace and hope through his art, leaving an indelible mark of character and sensitivity in every piece he creates.

For many years, GRK GALLERY has been actively promoting and selling the works of Ghass to collectors, media, institutions, museums, and foundations on an international scale. The artist is widely recognized and firmly established in the world of contemporary art, becoming a trusted and sought-after name among art lovers worldwide.

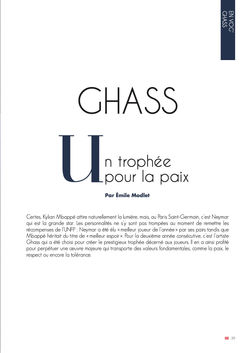

This singular artist is also renowned for his monumental works, his famous design of the Alpine A450, his Ligue 1 Best Football Player trophies since 2007, as well as his recent Marianne installations, symbolizing Woman, Life, and Freedom across the world in tribute to women’s rights globally. His journey continues with promising new projects, further solidifying his position as a renowned artist and a reliable figure on the international stage.

Thomas Schlesser

is an art historian, director of the Hartung-Bergman Foundation, where he "has the mission of ensuring the conservation and enhancement of the thousands of works, archives and architectural heritage of the property of Antibes , designed by Hartung »

For Ghass, creativity hinges on a deep motivation, a necessity; in his painting one senses an urgeny, that of giving shapes – not necessarily the same thing as giving – to his vision of the world.

Is there anything worse than finding ourselves confronted with a work and the realisation that the artist has nothing to say? We cannot feel more bitterly disappointed space – visual, literary or musical – is occupied by something and for nothing. And worse still, we often see that the creator of the catastrophe believes he is giving himse lf to us as part of the world of creativity. He is deluded. For he is only taking from the viewer – taking his time , energy, money – as he dupes him with trivia that are decorative, playful, entertaining, vague, and vaguely pleasing to the eye.

Ghass has known war, violence and painting. His aesthetic is viscerally suffused with the barbaric. For most of the elegant spectres who haunt private views, this is doubtless no more than a detail, a mere trifle: who among them is capable of imaging the taste of blood in the throat? Yet what Ghass has become is a lanus who has moved from the spectacle of the madness of armed combat to that of the arts. And the spectacle he offers in return is eloquent.

This is no ordinary journey, even if it has become regrettably more common down the centuries, with conflict so often gaining ground at the expense of peace. Thus the first world war brought the blooming, like flowers on an ash-heap, of the greatest poems – those of Apollinaire – and of such great artists as Otto Dix, Marcel Gromaire, and Henry de Groux. This is but one of countless examples.

From death to life, from despair to the future, from destruction to creation; the transition from war to war is symbolised by Janus, the two-headed Roman god.

To convey the terrifying echoes of violence with such economy of means – all is pared down to black, red and white – requires work that is unrelenting, dedicated, and constantly renewed. This is precisely – and rewardingly – what Ghass’s oeuvre brings us. There is no point in overstatement when your vision must fluctuate between the song of the bombs and the cries of the heart.

The tension between this simplicity and a multiplicity of meanings – sometimes in conflict, as in life itself – underlies the distinctiveness of Ghass’s painting. Beneath its apparent austerity, this tension also attests to a subterranean complexity in which truths exist only approximately, lines zigzag and, the invisible seeks to show itself as the visible seeks to disappear.

Ghass has much to say in his oeuvre, and listening to him is not easy; for where some believe that a moralising point of view is enough to settle an issue, he questions ceaselessly. His painting is, as Ronald Barthes once put it, “this very fragile language that men set between the violence of the question and the silence of the answer”.

ALPINE A450 24H LE MANS DESIGN TROPHY FOR THE BEST PLAYER BY GHASS

PRESS ARTICLES

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |